Choosing Your Exercise

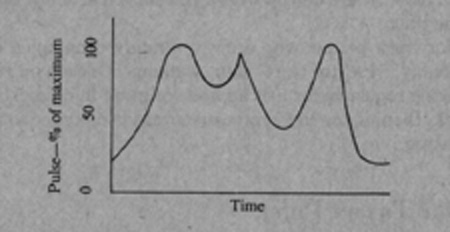

In choosing a form of exercise, the most important criterion is whether it will allow you to attain and maintain your target pulse over a fairly long period of time. Many kinds of vigorous exercise—tennis, baseball, vollyball, calisthenics—produce a pulse rate that varies widely. Over a few minutes of football, for instance, your pulse might vary like this:

Your heart works very hard—reaching far above your target pulse—for brief bursts, with rests in between. This pattern of exercise puts a great deal of stress on your heart, and has relatively little training effect.

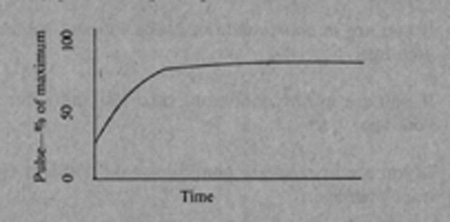

The reason that running, jogging, walking, swimming, and similar activities are the best conditioners is that they produce a pulse pattern that looks like this:

This pattern of continuous, steady exercise at a moderate, sustained level offers the best of both worlds—maximum training effect with minimum stress on your heart. After half an hour of exercise at their target pulse, most people will feel not exhausted, but refreshed. This slow, steady pattern with careful attention to not exceeding one's target pulse is, in fact, the keystone of exercise programs prescribed for patients who are at the very highest risk of having a heart attack—cardiac patients who have already had one.

When you read of someone having a heart attack while exercising, you can be fairly sure that he was pushing himself beyond the pulse level indicated by his age and level of fitness. Persons with diagnosed or suspected heart disease and persons with risk factors for coronary disease should be especially careful, and should check with their physician before starting any program of vigorous exercise. Risk factors for coronary disease include the following: chest pains, shortness of breath, dizziness, a family history of heart disease, low level of physical activity, smoking, history of rheumatic fever, heart murmur, high blood cholesterol, type A personality, history of abnormal electrocardiogram, chronic high stress levels, more than fifteen pounds overweight.

Pace

It took me three months of three-times-a-week practice to learn to exercise at my target pulse. For those three months, I had to stop and check my pulse about every ten minutes. For the first four to five weeks, it was too high nearly every time.

I finally learned to slow down by becoming more aware of the different paces I was capable of. It's very much like shifting gears in a car—the trick is watching the RPMs, not the speedometer.

I learned to go from ''compound low," a very slow shuffle, through a dozen varying gaits to "overdrive," a free-wheeling lope for coming down long hills. You can learn to "shift gears" in response to the slope of the road or trail, your energy level, your target pulse, and the messages you are receiving from your body. And you become much more aware of your body in learning to listen for these messages.

I also became aware that I was having ''slow days" and "fast days." I was usually discouraged by the slow ones, and sometimes became so overenthusiastic about the fast ones that I would overdo it.

My subjective experiences were verified when I heard about the "Inclined Saw-Tooth" theory of fitness training. This theory states that as one continues to train, one's fitness level does not increase in a straight line, but as a series of peaks and valleys—so that if you were to look at a person's progress over a long period of time, it might look something like this: